Is every soul born good?

This is the question which opens my novel Knight Crew.

I’d written a 150 pages of the book – my re-telling of the King Arthur legend set in contemporary gangland – when I was invited to a Music-in-Prisons event at Prison A. (This article first appeared as a guest blog on Candy Gourlay’s http://www.notesfromtheslushpile.com 2010)

At the microphone was a young, six foot four black man with biceps bigger than my (middle-aged, menopausal) waist.

This was OG, the leader of my gang, who I thought I’d made up. What clinched it was that the man (I’ll call him Khaine) was wearing a cut-off baby-blue T-shirt – the colour I’d chosen for my Knight Crew gang.

I don’t suppose I’m the only writer to have bumped into one of her creations, but it’s still pretty spooky. I asked Khaine if I could visit him.

Of course, even with Khaine’s consent, it wasn’t quite that simple. It took me about three weeks to understand the process of getting a prison visit. And a further five days and approximately four hours on the phone (this is not an exaggeration) to raise a human being with whom to book the visit.

Finally, I arrived with my shining face, my notebook and ten pounds to cover tea and biscuits. At reception I was told to put my notebook and my ten pound note in a locker. We’ll come back to the notebook. As for the impounded money – how was I to buy tea? I should have brought change. How was I to know to bring change? No answer. The nearest place to Prison A with change was 20 minutes walk away, I would miss my visiting slot. Could staff give me change for the note? No. Did any of the staff have any change at all? No.

In desperation, I offered to exchange my ten pound note for £2, for £1, for 50p even. A drawer opened. Nestling inside was a full tin of change. This encounter was to set the tone for almost all my dealings with the prison.

Several locks and clanging doors later I finally arrived in the prison visiting room. What did I hope for from my meeting? I’m not proud of this – but I thought Khaine might be able to help me with my street language, my gangland setting.

What we actually talked about in that first meeting was Africa. Khaine was born in Nigeria and had left aged four. My Guinevere character in the book (Quin) had been born in Africa and left when she was four. My spine began to tingle all over again. I asked Khaine to tell me everything he remembered from those first years of his life.

‘In Africa,’ he told me in that windowless room, ‘the sun is so bright you think there can’t be darkness anywhere in the world.’ That extraordinary line went straight into the novel and, much later, into the opera that Glyndebourne commissioned from the book. In fact everything in the novel that’s to do with oranges and bright sand and green lizards and spiders with shells on their backs comes – came – from Khaine.

Clearly, I’d had my money’s worth. But how had it been for Khaine?

‘Please visit again,’ he said, ‘there aren’t many people you can talk to in here.’

I went out of that room smiling. Not for long. In the courtyard before the main gate, I was pounced on by an officer. I had been seen writing ‘copious notes’. That’s what I do, I said, I’m a writer.

How did you get the paper? Having had my notebook bagged at reception, I’d asked for, and received, some loose leaf paper in the visiting room.

So I was an official visitor? Not exactly.

A social visitor then, a friend of Khaine’s?

Clearly I wasn’t ticking the boxes. The officer demanded to read my notes, take them away, photocopy them. Overawed, and feeling not a little intimidated, I let him do just that. There were things in those notes about Khaine’s offence – which, as he’d pleaded guilty, were probably well known to the authorities. There were also very personal things about his childhood. Afterwards, I thought I should not have let those notes be photocopied, not without Khaine’s permission.

I felt bad. It was to become a familiar feeling inside those walls.

Before I visited again, and operating at senior manager level (switchboard: why do you want to speak to him? Who are you? What organisation do you represent?) I finally got my notebook cleared. I could go in to the prison with my own notebook!

Only somehow the message never made it to the front desk.

Every time I tried to explain myself I was met with suspicion. There are many rules and regs in prison (I’m sure there have to be) but nobody explains them to the humble visitor.

I like to be positive. I contacted the Head of Security (no, you can’t have his name, or his e-mail address. Who are you? Why do you want to know?) with a few suggestions, nice cheap ones: maybe on the phone line (which could ring engaged uninterrupted for 50 minutes and then simply just ring. And ring) you could put an answer-message saying visits could be booked by e-mail?

It took me three months to find that out and then I only found out by accident. Perhaps, when you did get through to book a visit, staff could ask if it was your first time and, if it was, send you some information about what to expect – like to bring some change and watch for the white line on the floor.

What white line? Well, I missed it too, the first time I was searched for drugs. There was a man and a dog.

It was the man who barked: Behind the line!

What line? A curt nod at the floor.

Oh – if only I’d come in with my nose to the concrete, I would have spotted it.

Khaine, meanwhile, was sending me lyrics (very good lyrics) and bits of prose he was writing. I commented on his work and sent him books of poems (some of them never arrived, some were bagged up somewhere in the system and turned up weeks, or months, later in Khaine’s ‘effects’ – not that he was notified of their arrival).

Note for Head of Security – any chance of knowing what you are, and aren’t, allowed to send to a prisoner? I took to sending letters and parcels separately, hoping at least the letters would get through. If I attached stamps, which I often did, I wrote STAMPS in giant felt-tip beside them, because they could go missing too. Khaine advised me to staple things. If you staple things, he said, I can see there’s something missing because of the two staple holes left in the paper.

I also, of course, sent the manuscript of Knight Crew. I even got clearance to allow Khaine to bring his copy, marked with criticisms, to visits. Only when he told officers his side of the wall, that he had permission to bring the manuscript to the visiting hall, they didn’t believe him. After all his work on the script (turned out his street language was pretty good, after all), he came empty-handed. Drip, drip, drip of suspicion, of disbelief.

I began to be careful what I wrote in my letters. They were being opened. By contrast, Khaine’s letters to me were often delightfully frank. In one early missive he described going on a medical visit:

Well, I was taken from A to B hospital for a hearing test. I’ve never seen A or B really. I had to fight tears, I think, from coming. It is so beautiful to behold. I was handcuffed to a prison officer half my size. Everyone was looking at me like I was what lay in wait outside their beautiful city in the dark. They shielded their children and guarded their wives lest this black giant demon from the other place wreak its vengeance upon the fluffy creatures of the light. A lady did smile at me. A doctor. I suddenly realized….I too was human, just a little bigger, a little bigger but human nonetheless.

If that was a good day, there were many bad days. Some of the darkest of which were in the January when Khaine’s court date was suddenly moved to July. As he’d pleaded guilty, and was therefore just awaiting sentencing, that meant another seven months of not knowing how long he would have to serve.

For six weeks nobody needed to lock Khaine in his cell, he locked himself in. He didn’t write, he refused visits, he couldn’t, he told me afterwards, even talk.

Spring came, I sent in a sprig of apple blossom (never arrived – taken apart petal by petal by the man with the dog probably), but gradually Khaine returned to himself and correspondence began again.

By now, Knight Crew was doing the rounds of the publishers. I’d made my senior gangster black, my hero (or anti-hero as he’s a murderer) mixed race, and my Lancelot character – the in-comer to the gang, the good man with the fatal flaw – white.

With a particularly big politically correct hat on, one of the publishers worried about ‘hero’ Lance being white. I shared this concern with Khaine.

‘Lance is my favourite character,’ he said, ‘the one I feel most close to.’ I was busy computing this remark (yes – of course you relate to Lance, because you too are a good man who made one catastrophic mistake), when he added; ‘because that’s what it’s like to be black – you’re always the outsider’.

Then a marvellous thing happened. Glyndebourne, who have been doing sterling education work in Prison A for over half a century, decided that all their Education work for the year would be based round Knight Crew.

There was a two day workshop planned where I, alongside a musician, would work with the prisoners to make lyrics and music for the piece. As I was in first draft of the libretto for Knight Crew the opera, nothing could have been more exciting for me. And how perfect, I thought, for Khaine, whose first love was music, lyrics. I briefed him immediately – watch out for the list to sign up for the event.

The workshop date grew closer and closer – Khaine hadn’t seen any list, where was he to sign up? I e-mailed the prison to ask the same question. No response. I rang to ask. The phone was slammed down on me. Well, of course it wasn’t quite like that. There was the semblance of a conversation first.

Me: I gather the drill for Glyndebourne education projects is for men who want to partake to sign up. I’d really like Khaine to be able to take part, what does he need to do?

Her: It’s not up to you to decide who comes on the course. BANG.

I stood astonished. I’ve given workshops in numerous different settings over the years (schools, arts institutions, pain clinics) and I’m used to being treated with professionalism, courtesy, enthusiasm even. What could possibly have gone wrong?

Later that day – the day prior to the event – I received a message: your involvement in the project is now officially over. Why? Why! Prison regulations state that you cannot both be employed in the prison and be a visiting a prisoner here.

I couldn’t believe it – because even if it was true (though such a regulation sounded far-fetched even for the prison system) it didn’t exactly take account of my and Khaine’s relationship which, after all, had arisen from a prison education project. Surely it could be sorted out with a phone call to the senior manager who (thanks to my ‘be positive in prisons agenda’) now knew me? He was out for the afternoon. Four hours in which to verify or challenge this ‘regulation’.

I started with the internet. It would take hours, weeks, to sift through all the regulations that loaded.

I tried my barrister friends: they were either in court or confessed, ‘it’s not exactly my specialist subject’.

Three hours left. What about the Ministry of Justice press office – surely they would know?

I rang through.

Are you a journalist? Yes. Not exactly a lie, all writers do occasional journalism. Who for? Freelance. Next – the all important question: can you work in a prison as well as visit an inmate there? Why do you want to know? I told the story of what was happening in the prison, but I told it in the third person, as though it was happening to someone else.

Why did I lie? I’ve thought about this so much since. The slick, quick answer, is I wanted information fast and, I believed, this was the only way to get it. The deeper, and much more scary answer, is that I had finally become the person the prison had always suspected me to be: dishonest. That’s what I learnt that day, that if you consistently expect the worst of people (as the prison system does) they will deliver to your expectations.

An hour later I had a very irate Ministry of Justice boss on the phone. She knew the whole story – I was not a journalist, I was the writer at the centre of the ‘story’. I was to lay off her staff and her office. Bang. Bang to rights, in fact. Ring ring, – oh the manager who knew me was back at his desk, a word to the new Head of Security and yes, the workshop could go ahead after all. Hooray. God bless this individual, the beating heart at the centre of the machine.

It turned out that the workshop was to be held in the detox unit (the reason why there had been no list – detox is a secure unit, such an easy thing to explain, had anyone thought to do so). I was told that because the event was voluntary and many of the men suffering withdrawal symptoms, we probably wouldn’t have much of a turn-out.

In fact, twenty-five men turned up. I began by reading the relevant chapter from the book but, fearing short attention spans, I read very fast.

One prisoner asked me to slow down: ‘Can’t you see,’ he said, ‘we’re all on the edge of our seats?’

When I finally stopped speaking, they actually applauded. Writing is a lonely business, I’ll admit to being chuffed. We started on the process of dividing up the story, letting the men put it into their own words, begin soundtrack work.

After lunch, we were denied access to the prison. Some irregularity in my colleague’s paperwork this time, apparently. Ha ha. Locked OUT of a prison?

By the time we were re-admitted our two and a quarter hour scheduled slot had reduced to 45 minutes.

The men, who had given up other opportunities (eg gym) to be at our event, were restless bordering on angry. I would have been too. I had been warned that there would be far fewer men in the afternoon but actually more men turned up than for the morning slot. For some though, the waiting had proved too much, they’d thrown in the towel.

One prisoner, however, had kept the faith, writing 16 lines of poetry I would have been proud to have penned myself. We cracked on: the men worked together, experimenting with track sounds to get the right ‘feel’ for their part of the story, laying them down in anticipation of the final event on Friday morning when words and music would come together.

At the end of the day, Education staff told us to pack away our gear, we would not be returning the following day. Why? Why! In answer, I was separated from my professional colleagues and marched in silence through a succession of locked doors for an audience with the Head of Security. I felt like a naughty schoolgirl, my heart pumping in my chest.

You know, he said, why you’re here.

Actually, I had no idea. There were a selection of crimes. One was to have ‘passed a note’.

This is what had actually happened. I’d praised the prisoner who had written the 16 line rap-poem. He’d glowed – asked me to take the lyric away with me. It was a gift from a man who, I’d thought, probably didn’t have many gifts to give right then. I’d wanted to accept, but I’d also wanted this man to take this poem back to his cell and remember how good a writer he was.

A member of staff kindly offered to photocopy the piece. On the prisoner’s copy I’d written: ‘You are a wonderful writer – a Knight Crew Star’.

That was the note. That was the sin.

Compiling this article prompted me to find the original poem. It contains the phrase: ‘Power I felt going through my veins, was like I’d been plugged straight into the mains’. I’d forgotten this line, but it wormed it’s way into the final libretto as: Wired. Electric. Jacked straight into the mains. Briggsy – if you’re out there, thank you.

Back to my crimes. It had also been reported that I’d given an inmate a hug. The man concerned had just told me his mother, aged 56, had died of leukaemia.

As it happens, my 56 year old mother died of cancer too. I think I was having a human moment. An intelligent and humane man, the Head of Security heard me out. He even believed me, I think. So we could go back and finish the workshop? Sadly – no.

The following date I wrote a ‘more in sorrow than anger’ note to the Head of Education. Actually, I was mad as a flea. What really upset me was thinking that no explanation would be given to the men. It would be just one more time that they would be let down by the system.

At the exact time I was supposed to be writing lyrics and making music, I went for a long walk with the dog. At the edge of some woods, I came across a Larsen trap with a crow inside. I know that crows are pests and farmers are legally entitled to set traps for them (I checked with the RSPB). But there are certain rules and regs. This ‘decoy’ bird had no water. It had rubbed its head so hard against the bars of its cage, its skull was featherless and bleeding.

That bird, I thought, is Khaine.

That bird is the let-down workshop men.

That bird is me.

I sprang the trap, held a door open for the bird. ‘Fly,’ I screamed at it. ‘Fly away!’ Probably more scared of me than of its freedom, the bird stayed put. ‘Fly – fly, fly!’ And finally – it did. Soared into the air and with it, my heart.

Soon enough July came and Khaine’s trial. Khaine’s solicitor thought that because of the 14 months he’d spent on remand, plus the fact that he had no previous convictions, had pleaded guilty and been a model prisoner, he might walk free.

I’d added my voice to that hope for, writing to the judge to give a character reference. I included a verbatim account of what Khaine had told me about the offence:

I have no-one to blame but myself. I did it, I regret it and I will never do anything like that ever again.

Then he paused and added:

I would have felt like that even if I hadn’t come in here.

Surely a candidate for rehabilitation in the community. I was in court to hear the sentence.

Five and a half years.

Even Khaine’s barrister was stunned.

Khaine had spent two periods on remand, both obviously to be deducted from the final sentence. ‘You do the maths,’ said the judge. The barrister was on his feet, on the spot. He added up the figures – incorrectly. I wanted to put my hand straight up – but I thought it might be contempt of court. I also thought someone else in court would tug the barrister’s sleeve, or, at the very least, that the mistake would be spotted when the paperwork was sorted.

No such luck.

Prison A is a predominantly a remand prison. Khaine was transferred to Place C. My round trip for visiting increased from forty-five minutes to two and a half hours. Khaine was back in a hole and his release date was wrong. Only by two weeks, but two weeks is two weeks.

Khaine raised the issue inside the prison. No-one believed him. With Khaine’s permission, I wrote to his solicitor, explained what I had witnessed in court and asked for advice. He responded by sending Khaine a written note of the correct dates (albeit he added 45 and 465 and came to a total of 507 days – but let that pass) and suggested Khaine show it to his wing officer. Khaine did. It made no difference. I tackled the solicitor again. He e-mailed: ‘I don’t see how I can do anymore’.

I continued to fret; somewhere in the system, I conjectured, there must be an official piece of paper with the date wrong – but where?

Eventually, I shared my frustration with a friend who is a lawyer for a national newspaper. She listened, she believed me. ‘The mistake was the barrister’s,’ she pointed out, ‘why not approach him?’ Genius idea – why hadn’t I thought of that? I asked for the barrister’s details. This (or maybe the remark about the national newspaper) seemed to galvanise the solicitor. He set to work .

Five months after I’d first raised the issue, I received news: the Court had re-issued a revised count of the remand period.

Why did it matter so much to me? Partly because it was a matter of natural justice. But also because, with the incorrect release date, Khaine would still be in prison when Knight Crew opened. With the correct date – he would be free.

Khaine meanwhile had been moved again. This time to an open prison in the Place D. Round time for visits now over four hours. But Khaine was eligible for ROTL – Release on Temporary Licence, which meant I could take him out of the prison for a day.

Where would we go? What would we do? Would it be safe? Yes, it’s shaming to admit it, but I was frightened.

It’s one thing to have a relationship with a man convicted for five and a half years under the watchful eyes and keys of prison staff, quite another to be wandering about alone with him. But if I was concerned, my family’s anxiety level was stratospheric – which was lucky, it meant I had to occupy the ‘I’m sure it will be all right’ place. Besides, wasn’t it time for me to trust Khaine the way I’d asked the judge to?

The day came. I choose Castle D as our day trip venue. Very public, family orientated and interesting too. Khaine had never been to a castle. We made an odd couple, I’m sure. Middle aged white woman with strapping young black lad. You could almost see the eyebrows rising.

We walked in the gardens, looked at peacocks, did the maze (Khaine was really good at the maze), talked to volunteer guides about the books in the library. It was fun.

One thing I noticed: when I left Khaine (to buy tea, look at something he wasn’t looking at) the atmosphere changed slightly. Parents noted the ‘giant black demon from the other place’ and they shielded their children. They really did. I was astonished. Or naïve. Or both.

Eventually, ten days before the opening night of the opera, Khaine was released. He took a train to X, to be with his family. We spoke on the phone. That was a magic moment. That felt like freedom.

We discussed the opera – would he come? Yes, of course. I sent him £230 to cover train fares for him and his mother (who had offered to accompany him), plus something for food and taxis. It occurred to me that if I’d recently left prison and someone sent me £230 I might just go down the pub. I didn’t think Khaine would do that but, if he did, I reckoned that was his choice. He’d earned the money.

Meanwhile, I got onto the job of booking him accommodation in Place A for the night. The charming proprietor of a central B&B had a room available, the only problem was, she had to be out that afternoon. She always liked to welcome her guests in person – this would mean leaving a key for Khaine. She didn’t normally do this unless she knew the guest concerned.

Was Khaine my friend? I thought about that. Well, he wasn’t my friend as in one of the people I’ve known and loved for thirty years. But if you call someone a friend with whom you’ve shared many deep things – then yes, he was my friend.

So he could be trusted with the key? To tell her, or not to tell her, that the last time Khaine was in Place A, his keys were all on a jailor’s ring? Not to tell her. But I did take a mental step backwards. If my house was empty, would I be happy to leave a key for Khaine to let himself in? If the answer to this was yes (and it was) then I could assure the owner of his trustability.

Yes, I said, you can trust Khaine with the key.

Khaine texted me from the train. He was on his way, but he was coming alone because his mother had managed to scald herself with a hot-water bottle and was unable to make the journey. Meanwhile, my youngest sister and her husband were also on their way.

As it was the First Night, I was going to have to take a curtain call, and therefore sit in a particular place in the auditorium. Would my sister and her husband be OK with looking after Khaine for me?

‘It would be a privilege,’ said my brother-in-law, in a moment that actually made me cry.

Some hours later, there he was: Khaine, on the hallowed terraces of Glyndebourne. It was so wonderful to greet him as a free man.

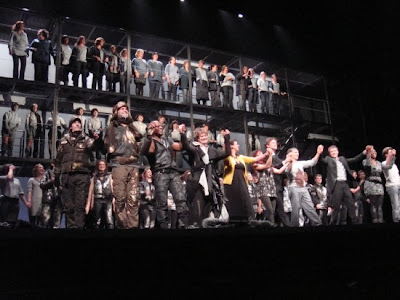

Another friend came by. A judge. I introduced them, she too had been at that first Music-in-Prisons event and remembered him. They got talking. It was soon time for curtain-up. The Knight Crew Chorus exploded onto stage singing about how they’d just ‘barrelled a car, blitzed a car’ on Saxon turf.

Barrelled. Blitzed. Two words from an encounter I had with Khaine in Prison B. I felt so proud, and so grateful to have him in the audience.

In the interval Khaine had another word with the Judge. ‘I never knew the human voice could sound like that,’ he told her.

A couple of hours and it was all over. Journalists scurried away to write their pieces (we were to have four star reviews in the Guardian and Independent and a call for a West End transfer from Gramophone), excitement was high.

Khaine came to say goodbye. ‘I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.’ ‘If you have trouble getting a cab,’ my brother-in-law said, ‘this is my number. Call me.’

I headed off to the First Night party. Half an hour later, Khaine turned up. No cabs. My boss at Glyndebourne had described the First Night Party as being for ‘the great and the good’. The good. I welcomed Khaine in.

I introduced him to the singers, the towering black figure of bass Robert Winslade Anderson, who’d played the Mordec/OG character and diminutive soprano Claire Wild who had sung her heart out as Quin, complete with the line,

‘In Africa, the sun is so bright you think there can’t be darkness anywhere in the world.’

It seemed the most natural thing in the world, Khaine being there.

When the party broke up, we drove Khaine to his B&B.

Back at home, my brother-in-law handed me a fistful of £20 notes. What are those for? Khaine gave them to me to give to you, he replied. It was the cost of his mother’s train fare.

A couple of days later, Yvonne Howard (who’d played my old bag-lady Merlin character, Myrtle) facebooked me to ask what Khaine’s name was. Why did she want to know (crumbs, was I turning into the prison?)? I was trying to describe him to a friend today, she said, all I could come up with was, ‘beautiful soul, warm, wise & gentle’.

I relayed that back to Khaine:

Awwr, Thank you very much… To be in such company really made me feel like I used to feel and that life is what one makes it.

I’ve thought long and hard about the purpose of this article; whether it will help or hinder the work writers and musicians do in prisons, make it more or less likely for governors to fear the writer’s notebook?

I have also, of course, thought about Khaine. Naturally, I’ve sought, and he’s given, his permission. Why wouldn’t he? Our relationship is one of truth and trust. But I don’t suppose he’d be that difficult to track down.

What if it results in his past life being splashed across the tabloids? Nothing would be worth that.

But then again, I don’t want to live in that world, a world where we are fearful of speaking out, where we are cowed, where we can’t trust.

The whole story of Knight Crew revolves around the question whether somebody who has mortally sinned (my Art’s a murderer) can ever be good again?

Art gives it his all, builds around himself (as in the original Arthur legend) a golden age of possibility, only to have it come crashing down because of the betrayal of his Queen and his dearest friend.

In one of the last scenes of book, the girls – who will not be defeated – light candles in memory of the dead, float them on the river.

In the opera they sing:

Someone has to hope, someone has to believe….someone has to see, someone has to look, someone has to write a new world in Myrtle’s book.

Is it too much to ask?

This piece originally appeared on the Notes From The Slushpile website

Right here is the right site for everyone who would like to find out about

this topic. You know so much its almost hard to argue

with you (not that I actually would want to…HaHa).

You certainly put a fresh spin on a topic which has been written about for many years.

Wonderful stuff, just wonderful!